India is positioning itself to play a larger role in the global semiconductor supply chain, driven by lessons from the Covid-19 pandemic and a growing need for technological self-reliance. While the country is already a global hub for chip design talent, it is now taking its first concrete steps toward manufacturing key components of computer chips.

India’s Strength in Chip Design

For Arnob Roy, co-founder of Bengaluru-based Tejas Networks, access to reliable semiconductor supplies is mission-critical. His company builds the electronic equipment that powers mobile networks and broadband infrastructure—systems that depend on highly specialised telecom chips.

“Telecom chips are very different from consumer chips,” Roy explains. “They handle enormous volumes of data simultaneously and must operate without failure. Reliability and redundancy are non-negotiable.”

India has long been strong in this design phase of chip development. An estimated 20% of the world’s semiconductor engineers are based in India, and nearly every major global chipmaker runs large design centres in the country.

“India is deeply involved in cutting-edge semiconductor design,” says Amitesh Kumar Sinha, Joint Secretary at the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology. “But manufacturing has been our missing link.”

The Manufacturing Gap Exposed by Covid-19

Despite its design expertise, India relies heavily on overseas factories—mainly in Taiwan and East Asia—to manufacture its chips. This dependency became a serious vulnerability during the pandemic, when global supply chains were disrupted.

“Covid made it painfully clear how risky concentrated semiconductor manufacturing is,” Roy says. “When chips disappeared, entire industries were forced to slow or shut down.”

The crisis prompted the Indian government to accelerate plans for a domestic semiconductor ecosystem aimed at improving resilience and reducing dependence on imports.

Where India Is Entering the Chip Value Chain

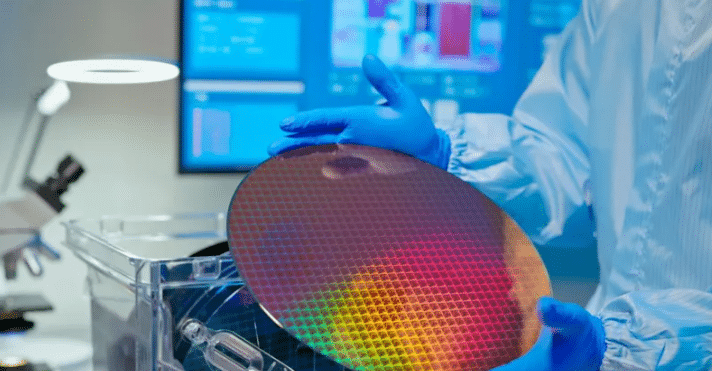

Chip production involves three main stages: design, wafer fabrication, and assembly, testing, and packaging. While wafer fabrication—often called “fabs”—requires massive investment and cutting-edge machinery, the final stage is more accessible.

India has chosen to focus first on Outsourced Semiconductor Assembly and Test (OSAT).

“Assembly, testing, and packaging are easier entry points than building fabs,” says Ashok Chandak, President of the India Electronics and Semiconductor Association (IESA). “Several OSAT facilities are expected to reach mass production this year.”

Kaynes Semicon: A First Mover

Founded in 2023, Kaynes Semicon is among the first companies to operationalise this strategy. Backed by government incentives, the company invested around $260 million in an assembly and testing plant in Gujarat, which began production late last year.

“Packaging is not just putting a chip in a box,” says CEO Raghu Panicker. “It’s a 10 to 12-step process. Without this stage, a silicon wafer has no industrial value.”

The facility will focus on chips used in automobiles, telecom networks, and defence systems—rather than cutting-edge smartphone or AI processors.

“These may not be glamorous chips,” Panicker notes, “but they are economically and strategically critical. You build scale first, then move toward complexity.”

Skills and Culture: The Biggest Challenges

Building a semiconductor industry from scratch has not been easy. India had never previously built a full-scale semiconductor cleanroom or trained workers for such specialised manufacturing.

“Semiconductors demand extreme discipline, documentation, and process control,” Panicker says. “The cultural shift is just as important as the technology.”

Training remains the biggest bottleneck. “You can’t compress five years of experience into six months,” he adds.

A Long-Term Vision for India’s Chip Industry

Back at Tejas Networks, Roy is optimistic about the road ahead. He expects a growing share of locally manufactured chips to support Indian companies over the next decade.

“I believe Indian firms will eventually design and manufacture complete telecom chipsets,” he says. “But this is a long journey. Deep-tech industries need patient capital and sustained support.”

India’s semiconductor ambitions are still in their early stages, but with strong design talent, government backing, and early manufacturing successes, the country is laying the groundwork to become a meaningful player in the global chip industry.